The fault lies not in our genes, but in our microbiome

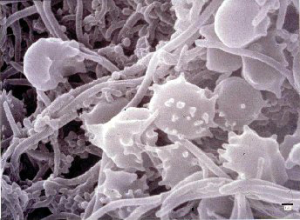

Conceptualizing humans as an organism, the microbes living within and on our bodies are often neglected. A recent trend in academia has been the research into the wide variety of micro-organisms living within and upon humans. Overlooked until recently, differences in the human microbiome are implicated in many disease states from auto-immune disorders to obesity. Some day is may be possible to lose a few pounds just by consuming the right mix of bacteria to colonizes your gut!

Given the advent of low-cost, high-throughput sequencing and the relatively smaller genomes of micro-organisms, a plethora of studies have been done comparing microbiomes of healthy and sick patients. First academia must answer the chicken-or-the-egg-question: do people have these diseases because of the combination of bacteria they have (or don’t have) or does having the condition lead to the combination of bacteria? Does the microbiome of a sick patient arise from having a specific microbiome or does being sick lead to the presence of the specific microbiome?

To test this question, sickened laboratory animals have been inoculated with the microbiome of healthy animals. Generally, the answers point to the idea that the right combination of microbes can alleviate the symptoms of a disease. The list of non-infectious diseases (allergies, asthma, diabetes, and obesity) that have been effectively treated by reconstituting the microbiome in laboratory animals is growing. While academic research on this area is booming, what practical progress has been made on this front?

Compare the number of clinical trials using fecal transplants (46) to those using a cell therapy (29,268). Clearly there is much room for growth in the practical application of the human biome to disease states.

Additionally, these initial clinical studies are looking only at the microbiome of the lower gut. This leaves many areas of the human anatomy unstudied. What about the skin, upper gastrointestinal tract, hair, eyes, nose and other mucus membranes? While academia is well on the way to working on these issues, little has yet been seen in the way of practical application of this as evidenced by the lack of clinical trials.

DeeAnn Visk, Ph.D., is a freelance science writer, editor, and blogger. Her passions include cell culture, molecular biology, genetics, and microscopy. DeeAnn lives in the San Diego, California area with her husband, two kids, and two spoiled hens. You are welcome to contact her at deeann.v@cox.net